TOPICS

Pandemic strategies in COVID-19 – containment, mitigation, herd immunity, uncoordinated

By Elizabeth Alvarez

Countries followed a variety of overarching strategies. These include containment, mitigation, herd immunity, and uncoordinated. While these names are often used interchangeably, as a Working Group, we use these terms to encompass the following objectives within countries:

Containment (also called elimination) holds that the country’s aim is to get to zero new community transmission cases. China and New Zealand are successful containment examples.

Mitigation is where a country aims to keep numbers of transmission low so that society at large, and specifically, healthcare systems, can keep functioning. Canada and France are examples of countries aiming to mitigate COVID-19. Herd immunity is an approach of allowing the infectious disease to run its course so that 70-80% of a country’s citizens have had the disease and become immune. This slows down a potential next epidemic.

Herd immunity is a term typically used for immunizations, where a percent of the population has to be immunized in order to protect “the herd.” Sweden was considered to follow a herd immunity strategy at the beginning of the pandemic, but even with that, there were societal changes that took place and later policy changes. The United Kingdom also started with this strategy but quickly changed course to mitigation as the number of cases increased and governmental officials became sick with COVID-19.

An uncoordinated approach is exactly that, one in which a country either does not have a strategy or changes strategies often or offers contradictory approaches in a way that makes it difficult for citizens to understand the preferred approach. The U.S.A. and Brazil are examples of disorganized strategies where different messages were conveyed by different levels of government.

Preparedness for pandemics

By Elizabeth Alvarez

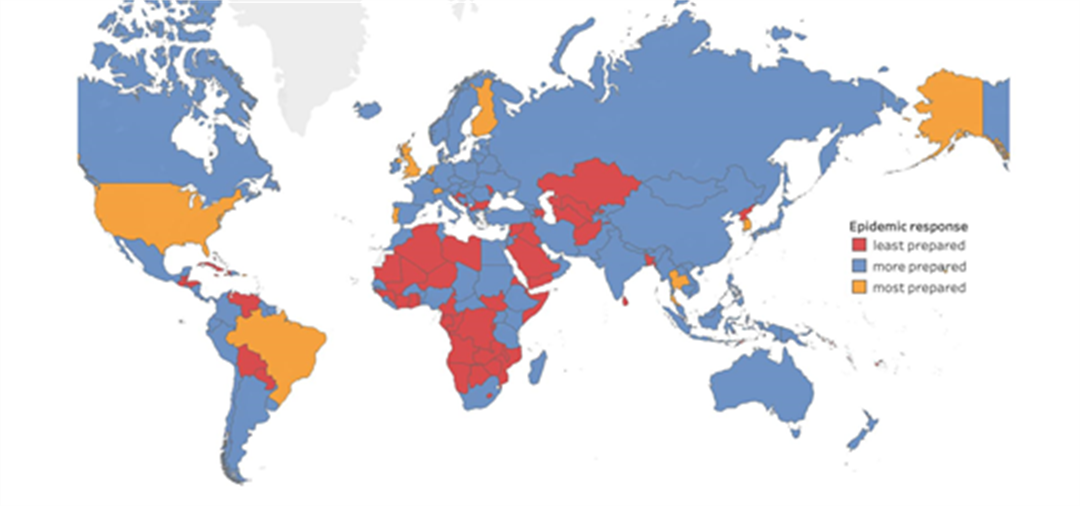

The Global Health Security Index is a comprehensive assessment of 195 countries in their global health security capabilities. The index has subcomponents for: preventing the emergence or release of pathogens; early detection and reporting epidemics of potential international concern; rapidly responding to and mitigating the spread of an epidemic; sufficient and robust health sector to treat the sick and protect health workers; commitments to improving national capacity, financing and adherence to norms; and risk environment and vulnerability to biological threats.

These are all important aspects in the prevention and management of an infectious disease epidemic. The map shows the scores by country for emergency preparedness and response planning in an epidemic (under respond). Notably, the United States of America (USA), Brazil, and the United Kingdom (UK) were in the top 15 ranked countries within the ‘most prepared’ category, and China was ranked 38 in the “least prepared” category.

In the overall ranking, the USA (rank 1; score 83.5), UK (rank 2; score 77.9), Canada (rank 5, score 75.3), Sweden (rank 7, score 72.1) were in the “most prepared” category. Brazil (rank 22, score 59.7), Mexico (rank 28, score 57.6), New Zealand (rank 35, score 54.0), and China (rank 51, score 48.2) were in the “more prepared” category, and Djibouti (rank 175, score 23,2) ranked in the “least prepared” category.

Authoritarian vs. democratic governments

By Peter Miller

COVID-19 has had global impact, affecting all countries around the world. The type of government may have influenced the perceived social and policy tools available to respond to the spread of infectious diseases. Democratic governments tend to permit greater freedom of speech and freedom of the press which allow for an open redress of grievances while authoritarian countries are considered to be able to stifle dissent. Democratic governments are made of representatives elected by the general population to whom they are responsive. Representative governments may thus show less willingness to enact drastic policy changes to resist COVID-19 while more authoritarian governments may be willing to take drastic measures once the threshold to act has been reached. However, in reality, the COVID-19 response may have been hindered by an unwillingness to acknowledge the problem or to act by either type of government. China is an example of an authoritarian government, whereas New Zealand and Australia are democratic governments, that used containment strategies for COVID-19.

Political systems – Political leaning

By Peter Miller

Governments around the world approach questions of resource distribution, social values, and maintaining organization, emphasizing different solutions and identifying different problems. Libertarian vs. Collectivist governments may emphasize different balances between individual freedoms and social obligations in responding to a collective crisis. Non-pharmaceutical infection control initiatives may receive widespread government support or be viewed as a matter of personal responsibility, leading to lower public compliance with health regulations. Economically Left vs. Right governments differ in the degree to which they accept the need for welfare support for the poor, vulnerable, and marginalized. Compliance with government restrictions is often contingent on being able to make ends meet, affording food, shelter, and other necessities which may not be possible without either ongoing employment or government support. Religious vs. Secular states may value human intervention in the spread of disease or consider it the will of the Divine. A Religious state and society may acknowledge the spread of disease, but not perceive it as a problem for the truly righteous or feel that intervention is simply pointless in the face of Divine providence. Patriarchal vs. Egalitarian societies may also differ on the importance of responding to disease. A state that highly values machismo and masculine values may ignore the impact of COVID-19 due to the associated cult of personal strength and invulnerability.

Trust in government

By Donna Goldstein and Stephanie Hopkins

Our project uses the Our World in Data indicator known as ‘trust their national government’ as an important indicator of citizen faith in national government and too, as a comparative indicator critical to framing differences across the diverse national sites we study. Within Our World in Data (ourworldindata.org/trust), there are many different kinds of indicators that propose definitions related to trust—between citizens, between individuals and medical practitioners and institutions, and between citizens and police. While ‘trust’ of many forms configures faith in the polity, for the purposes of our study, we focus on one particular indicator with that of the share of people that trust in their national government (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-who-trust-government).

The trust in national government indicator divides the globe into five equal 20-percentile categories, with cut-off percentages at each 20 percentile mark. The indicator shows the share of people that trust their national government, and thus a small share of people indicating trust—under 20%—would indicate low trust. At the other end of the spectrum there are countries with the share of people that trust their national government—above 80%—indicating that a large share of the respondents have “a lot” or “some” trust in their national government. The indicated share of respondents can inform us about how people in different nation-state contexts relate to their national context, helping us interpret how individual and collective understandings of COVID-19 policies are co-configured with their sense of trust in national government.

If we consider the United States, for example, in 2018, approximately 43.47% of the population answered “a lot” or “some” to the question: “How much do you trust your national government?” Only 14.5% of Brazilian respondents, 17.22% of Greek respondents and 10.95% of Ukrainian respondents answered in that manner, exhibiting some of the lowest trust levels in their national governments (under 20%). In 2018, Switzerland (81.47%), Norway (89.09%) and Ethiopia (92.34%) exhibited some of the highest levels of trust in government as measured by the percentage of respondents answering “a lot” or “some” to the same question (above 80%).

We use this indicator to understand how national-level public health communications are interpreted by citizens in a national setting. Trust in government is activated when citizens are asked to interpret high-level communications emanating from government. Trust in government—in their own national government—is an important factor in the spread of COVID-19, as trust is the foundation to the legitimacy of government institutions and is key for maintaining social cohesion. Government policy measures to control or mitigate the spread of COVID-19 often require or suggest a behaviour change, requesting that individuals limit personal freedoms. All policies, whether mandated or suggested, require some level of compliance by individuals on behalf of society. In times of uncertainty, governments must leverage public trust as a force for change. The trust in government indicator provides a sense of how individuals might adhere to government policies.

Risk communication

By Jean Slick and Marie Gedeon

In response to an emerging public health threat, there is a need to provide timely and credible information to the public about what is known and not known about the threat, potential consequences, and clear advice about the protective actions that can be taken to minimize harm. All across the globe, public health interventions were implemented to ultimately decrease the risks of morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19. Exposure risk, disease progression risk, access care risk, mobility associated risk, all various potential risks being communicated mostly through national and international channels (public health emergencies of international concern – PHEIC on a real-time basis), and domestically by several jurisdictions seeking to engage with the local communities in using communication tools to ensure that populations get access to health promotion, protection and education messages.

Health communication is an integral part of public health measures in health and safety management, environmental risk management and in infectious disease outbreak response. Risk communication is one of the 6 components of health communication. Broadly, health communication as defined by the European CDC encompasses 6 components. Risk communication is one of those 6 components; defined as a sustained communication process with a diverse audience about the likelihood of health outcomes and the susceptibility of shaping behavioral attitudes. Understanding and knowledge about an emerging threat will evolve over time, and hence risk communication is a dynamic process.

The effectiveness of communication is influenced by a number of factors including the source of the message, the content, the channel, and the audience perception of risk. For risk communication to be a successful component of health communication, populations must be able to access the information and to understand it. Other components of health communication include crisis communication, outbreak communication, health literacy, health education and health advocacy. Barriers to information comprehension and reception may include, education level, language and sociocultural barriers, misperceptions, and information consumption. Analysis of metrics about homelessness and internet access could capture the health disparities caused by adverse circumstances which the consequences of COVID-19 could have further magnified in disproportionately affected sub-groups.

Sources of information include official sources, from institutions such as WHO, CDC, local public health agencies, local authorities, with messages from these sources being disseminated via their websites (situation reports, documents produced – guidelines – recommendations), traditional media (mainstreamed news sources, the press, radio, television) and social media posts, all which can get further amplified through social networks.

Trust in sources needs to be established in advance of an event. In the Canadian context, papers on the subject of risk communication, regularly cite the WHO, the Canadian federal and provincial governments as trusted sources of information about coronavirus. Key spokespeople during the pandemic have included public health officials and political actors, with differences across jurisdictions in terms of who has taken the lead role. Medical professionals and scientific experts, who sometimes are identified as being closer to the public, may also play an important role.

The massive dissemination of information during the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in an “infodemic,” including global spread of misinformation, disinformation, and fake news, all of which pose serious public health risks and make public health messaging more challenging during the pandemic. Misinformation relates to inaccurate information on the prevention or management of COVID-19, whereas disinformation pertains to unreliable information which plays a role of propaganda (fake news), presenting emerging solutions with adverse effects, creating confusion and polemics in highly polarized political environments and media ecosystems. Countries such as the United States and Brazil are prime examples of such partisan polarization creating disinformation.

This unprecedented health threat that is SARS-COV-2, and its capability to mutate, will certainly provide lessons for the production of risk communication tools and standardized approaches to mitigate the impact of future health emergencies and disasters, to follow the outcomes of any communicable disease in an epidemic, to assess various governance modes in applying evidence-based science to crisis solutions, to reinforce the messaging of communities of experts, and to put health forward in all policies.

Role of media

By Japleen Thind, Stephanie Hopkins and Simrat Gill

Various forms of media have been integral during the pandemic. Public health officials used print, broadcast and social media to update the masses about the pandemic. As the pandemic worsened, the public sought information from the most accessible form of media – the internet. The internet provides vast opportunities for economic growth, improved health, better service delivery, and distanced education. Considering the importance of the internet in healthcare delivery and information communication, we collected data on individuals using the Internet (percent of population) from each jurisdiction. To get an insight into the freedom of expression within each jurisdiction, we collected data on the internet freedom scores, 2020 and the internet freedom scores status, 2020 (free, partly free, not free).

We also gathered data on world press freedom index global score, 2020 (scores range from 0-100, lower is better) and world press freedom index rank, 2020 (out of 180 countries, lower is better). These indicators give an insight into press freedom, which is the right to report news or circulate opinion without censorship from the government.

While the internet and press are common forms of information communication, cell phones are one of the most common means of accessing these forms of media. We collected data on mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people). Over the past decade, there has been a dramatic growth in telecommunications in many countries. Communication technologies are increasingly recognized as essential tools of development, contributing to public sector effectiveness, efficiency, and transparency.

A hypothesis on whether the greater or lesser access to media was advantageous or obstructive in the response to COVID-19 is still undetermined. While the media was used to promote physical distancing, telemedicine, and other important health and policy interventions, it also played the opposite role of impeding public health interventions through misinformation and disinformation, such as conspiracy theories.

Health systems

By Dhrumit Shah

The structuring of policies surrounding COVID-19 is reliant on the health systems in place. How the financial resources are working to adequately cover the cost of health needs of a system also comes into play. Health capacities in clinics, hospitals, and community care centres dictate the extent of aid that can be provided to patients seeking medical attention during a pandemic. Physician density (number of physicians per 1000 population) and hospital bed density (number of beds per 1000 population) are parameters that can assess a country’s health capacity. Healthcare accessibility, medical countermeasures, personnel deployment, and having an updated hazard risk and vulnerability assessment plan are essential when evaluating the preparedness for pandemics and availability of services for populations. Communication with healthcare workers during a public health emergency is important to mobilize strategies driven by medical knowledge. A nation’s ability to contain the transmission of COVID-19 depends on the types and timing of policies, testing, contract tracing and infection control practices established by health systems. Dealing with local outbreaks through educating the public about pandemic responses and implementing isolation or quarantine policies play an important role in this regard. COVID-19 detection and response are guided by the capacity of health systems to offer available and reliable testing techniques and vaccines by approving and using new medical countermeasures. Another important factor for the effectiveness of COVID-19 measures includes surveillance systems and reporting of the data.

Population factors

By Janany Gunabalasingam

Population factors are important contributors to the spread of COVID-19. Areas with high population density, such as metropolitan cities, increase the probability of individuals coming in contact with others, consequently spreading the disease at a faster rate. Furthermore, the prevalence of major health conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension and obesity, increases the risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes. Underlying comorbidities coexisting with COVID-19 can increase hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and mortality. Population age distribution can also influence COVID-19 case counts. Regions with relatively older populations may have increased risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes, thereby contributing to a larger proportion of hospitalization and COVID-19 mortality compared to population with younger average age.

Individual factors

By Kaelyn McGinty

Individual factors have been demonstrated to play an important role in determining who is most susceptible to COVID-19 infection.

Individuals of any age are at risk for contracting COVID-19. However, age influences social behaviours that may lead to higher or less risk of exposure. For instance, younger people tend to participate in larger social activities that can lead to an increased exposure of the virus, but are less likely to exhibit symptoms or suffer from a severe prognosis. On the other hand, older age is associated with increased risk of a severe or fatal prognosis.

Sex and gender influence the likelihood of an individual being exposed to COVID-19 and suffering from severe infection. Women tend to be or work in positions with close-contact or proximity and high exposure to infectious disease to a lesser extent than men. However, male sex has been found to be associated with more severe or fatal COVID-19 outcomes relative to females.

Certain health conditions and comorbidities have been reported to increase the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes. In our database containing country-level indicators, rates of hypertension, diabetes and obesity are provided by the World Health Organization. Rates of mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes or chronic respiratory disease, are also provided by the World Health Organization using 2016 estimates. In the context of COVID-19, obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, and chronic kidney disease have been found to be strongly associated with poorer outcomes and an increased mortality risk.

Racial or ethnic minority status may be associated with an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 and developing severe infection. This association is likely influenced by more than race or ethnicity itself, but rather larger systemic inequity and discrimination that places individuals of racial or ethnic minority status in vulnerable social, occupational and household settings that lead to increased susceptibility to viral exposure.

Education and income, or socioeconomic status (SES), also influence the likelihood of coming into contact with COVID-19. In our database containing country-level indicators, SES and educational attainment may correspond to rates of adult literacy, primary school enrollment and homelessness, as provided by the World Bank. In the context of COVID-19, individuals with higher income and educational attainment are less likely to work in essential roles with close contact or proximity to other people, use public transportation, or live in overcrowded households. On the other hand, individuals with lower income or educational attainment tend to work in essential service roles with closer contact and proximity, use public transportation, and live in communal or overcrowded settings. SES is also known to influence exposure to a variety of other health risks, such as occupational or environmental hazards, such as higher levels of air pollution, which may further contribute to increased risk of contracting COVID-19 or developing severe outcomes.

Vulnerable employment

By Kaelyn McGinty

Vulnerable employment may be characterized by conditions that pose a greater exposure to certain risks (ie. health, social, financial) than other types of work. In the database containing country-level indicators, rates of vulnerable employment for 2020 are provided by the World Bank.

In the context of COVID-19, certain conditions of vulnerable employment, such as a high workplace density or close-contact with other people, generate a greater risk of exposure to COVID-19 infection. Working conditions with limited income support, either by low wages or lack of paid sick leave, can also increase the likelihood of COVID-19 transmission and infection by preventing workers from foregoing “risky” behaviours in order to maintain a stable income. In addition, vulnerable employment rarely provides an opportunity for remote work, or ‘work from home’, leading to an increased risk of coming into contact with COVID-19 in the workplace.

Economic factors

By Katrina Bouzanis, Amr Saleh and Arwa Hilal

Economic factors play a role in individuals being able to follow public health directives, such as stay-at-home orders, purchasing and storing food in advance, work-from-home directives, and transportation to work. At a meso-level, businesses may be able to afford paying employees sick pay or purchasing protective personal equipment (PPE). At a macro-level, economics also play a role in COVID response. Gross domestic product and other national-level indicators play a role in governments being able to provide financial supports for businesses and individuals, offer social services, purchase and supply medical care, and carry out pandemic planning. Here are some of the indicators included in our database of COVID-19 policy-relevant factors.

- Index of Economic Freedom: The index of economic freedom takes into account twelve factors such as regulatory efficiency, rule of law, and government size to quantify economic freedom.

- World Bank Classification: The World Bank classifies countries based on GNI every year by assigning the world’s economies to four income groups; low, lower-middle, upper-middle, and high-income.

- GINI Index: The GINI Index measures the distribution of income across a population. The index is primarily based on the GINI coefficient, which ranks income distribution on

- GDP per capita: Per capita gross domestic product is calculated by dividing a country’s GDP by its population to provide a measurement of the economic output per person.

- GNI per capita

- Current Health Expenditure

- Vulnerable employment

- % Homelesness

- Adult Literacy Rate %

- Primary school net enrollment ratio

RELATED PROJECTS

Limitations of COVID-19 data – submitted manuscript, will be added once published

OTHER RESOURCES

UNESCO impacts of COVID-19 on education

Includes school closures, duration of school closures and where teachers are prioritized for COVID-19 vaccines: